Immanuel Ben Misagga

In the raw aftermath of any election, the world rushes to crown a victor and bury the vanquished. Headlines such as why so-and-so won and why so-and-so lost are commonplace.

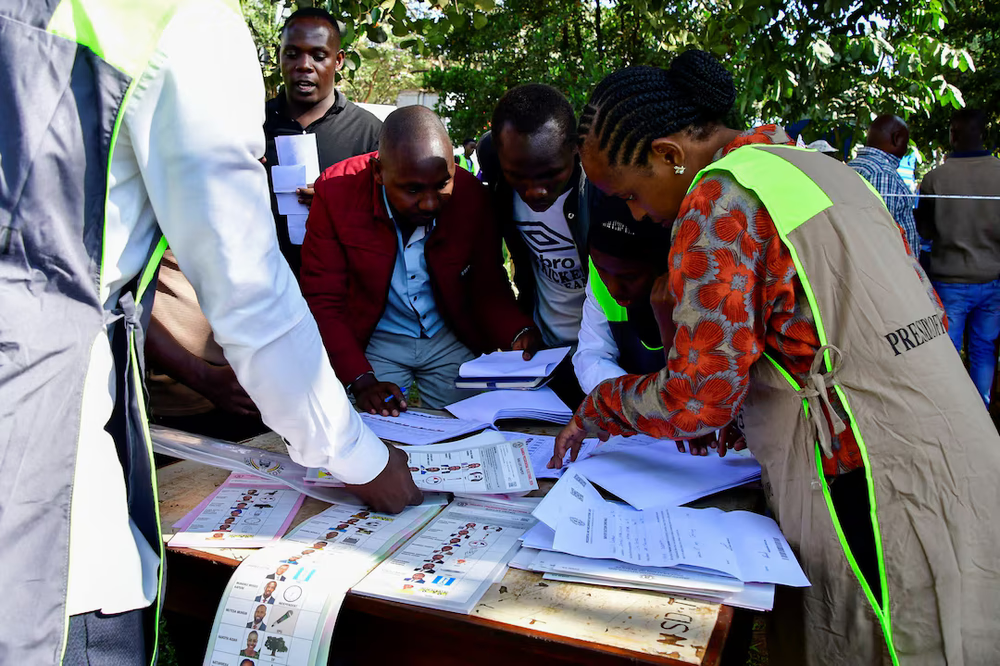

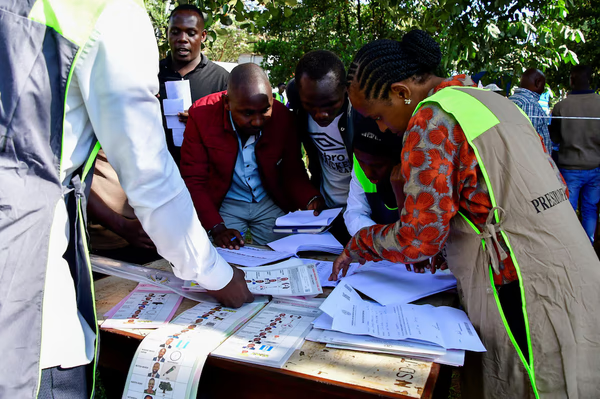

The 2026 Ugandan general election has been no different. Yet, to view January 15, 2026 merely through the lens of President Museveni’s seventh-term victory and the National Unity Platform’s (NUP) reduced parliamentary numbers is to miss the profound and potentially transformative political evolution unfolding before us.

What we witnessed was not a static repeat of 2021, but a dynamic contest that brought out the best in both the NRM and the opposition. This is a sign of a maturing political arena, and it presents a critical opportunity for national progress—if both sides are wise enough to seize it.

The NRM entered this race with its greatest vulnerability being the perception of a long-standing leader. Yes—40 years in power. Their response was not complacency but correction. They meticulously studied the “wrongs” of the 2021 general election that catapulted NUP into a political force, as well as grievances from within the party. Their strategists, led by the pragmatic Speaker Anita Among, engineered a campaign that ultimately consolidated their base and shrewdly exploited opposition fractures. She helped the NRM pull out several independents to clear the way for party candidates.

Just like the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa after the rise of Julius Malema’s breakaway EFF, the NRM has proved in the 2026 election that it is a learning institution—adapting to survive and maintain its dominance.

Throughout the campaign, the NRM candidate paid less attention to his opponents and focused instead on areas that had eluded his government, such as commercial agriculture, industrialization, and poverty eradication. It should not be forgotten that before the campaigns he had just completed a nationwide PDM tour. The two-month campaign period was merely a continuation of mass mobilization en route to the January 15 finale.

On the other side, the NUP and its principal, Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine), faced the Herculean task of transitioning from a protest movement into a credible, nationwide government-in-waiting. To their credit, they successfully solidified their position as the principal opposition force, annihilating breakaway factions and firmly owning their narrative as the “new breed.” Their surge in the court of public opinion is undeniable. However, in the crucial work of building a broad, cohesive coalition, cracks emerged.

For instance, NUP Secretary General Lewis Rubongoya (chief of staff in the army) had no business contesting as an MP without resigning his position. As it turned out, he and his deputy, Aisha Kabanda, spent most of the campaign period canvassing for their own votes instead of focusing on strategy for Kyagulanyi. This denied NUP the benefit of a unified and coordinated strategy. The fact that both Rubongoya and Kabanda lost is a classic testament to expanding effort in the wrong direction—both fell on the front line at the same time, effectively opening the front door.

The very act of solidifying their core may have cost several other NUP candidates vital constituencies. This should serve as a lesson in the delicate balance between purity of message and the arithmetic of power.

The 2026 election setback should be a precursor for NUP to form a think tank, manned by multi-opposition strategists, to evaluate their performance and design a watertight strategy for 2031.

So, where is the win-win in this result?

For starters, Uganda has another five years of NRM rule, but there are many positives to take from all sides.

For the NRM, the win is a clear—but costly—mandate. It is a mandate that comes with an explicit invoice: the electorate has shown that discontent can be organized. Victory is a license to govern, not to ignore. The “corrected wrongs” of 2021 must now translate into tangible, inclusive governance that addresses the very issues the opposition highlighted so effectively during the campaign. Stability is their prize, but accountable delivery is their new imperative.

I lost count of the number of times Speaker Anita Among addressed this issue at NRM rallies during the campaign—and she was not alone. Party Secretary General Richard Todwong consistently echoed the same message.

For the NUP and the opposition, their people spent much of the campaign fighting individual MP battles. Nonetheless, they have been stress-tested. They now possess invaluable experience and a clearer understanding of their strengths and, more importantly, their fault lines. NUP’s reduction in MPs—provisionally from 58 in 2021 to 48 in 2026—is not a death knell but a diagnostic report. It reveals where coalition-building failed, where messaging resonated or faltered, and what it truly takes to convert popularity into plurality across Uganda’s diverse political landscape.

Kampala and Wakiso combined may have more than three million voters and 12 MPs, but in political calculation it is of greater significance to win Karamoja-Sebei’s representation of more than 20 MPs from just 300,000 voters. That is the reality.

There is no doubt that NUP’s momentum is real, but it now requires engineering to convert it into sustained electoral power. How else can one explain the absence of a single successful NUP candidate north of Karuma?

The path forward therefore demands strategic solutions from both sides, for the ultimate benefit of Uganda in the years to come.

For the NRM, this term should be used to institutionalize systems—not personal authority or glorification. Actively create visible, bipartisan channels for addressing national issues such as youth unemployment and service delivery. A confident ruling party should welcome a strong, constructive opposition as a partner in national development, not merely as a foe to be diminished.

For the NUP, the answer lies in building, not just rallying. The next five years must be a relentless project of institutional development beyond the magnetism of its leader. Deepen policy frameworks, nurture grassroots structures across all regions, and master the art of strategic alliance-building. Learn from the ANC-EFF dynamic: initial shockwaves must mature into sustained, broad-based pressure.

Finally, for our democracy, there is a need to formalize the “correction” mechanism. Civil society and the electorate must champion a new norm where post-election analysis focuses on evolution, not just victory.

We need platforms that dissect why votes shifted—holding both sides to their promises and analyzing their adaptations with the seriousness of a national audit.

What 2026 has gifted Uganda is a blueprint for a competitive, responsive multiparty democracy. The electorate has shown it is watching, learning, and shifting its expectations. The trend is international: power is never permanent, and opposition is never futile. It is a pendulum.

The 71-percent win for President Museveni demonstrates that the NRM has corrected its wrongs—for now. Bobi Wine and the NUP now hold the blueprint to correct theirs by 2031. This healthy, tense, and dynamic balance is not the crisis of a nation, but the forging of one.

Let both sides read the results not as a final score, but as instructions for the next, more demanding level of our national contest. The true winner, in the end, must be Ugandans.

My grandfather in Kyotera, Kifuta, used to tell me how an egret keeps cattle, yet never eats meat or drinks milk. It is the cat that enjoys both, yet does not know where the pasture is located—never mind cattle feeding.

The author is a football investor and a vintage citizen.